IMAGE: Background, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, AFL-CIO Still Images, Photographic Prints Collection. Foreground, Resha T. Swanson-Varner. (1)

In honor of Black History Month’s 2025 theme, “African Americans and Labor,” we’re featuring HPRS scholar Resha T. Swanson-Varner (Cohort 2022), whose research examines the intersection of labor rights, racial justice, and policy in the American South. As a PhD student at the University of Chicago studying Social Work and Social Policy, Resha examines how Southern state legislatures use their power to block labor policies in predominantly Black and Brown cities. In this reflection, she shares her journey from personal experiences as a low-wage worker to becoming a researcher dedicated to understanding and challenging systemic labor inequities.

Resha T. Swanson-Varner

What is your research about?

How do we value labor? How do we ensure that every worker is treated with dignity? How do we create good jobs? How do we strengthen policy mechanisms that protect workers? These are the questions that guide my research. Specifically, my dissertation examines how conservative Southern state legislatures use their preemption powers to block labor policies (e.g., minimum wage increases, paid leave, fair scheduling) originating from liberal Black and Brown cities. I also study the locally organized responses to these preemption attempts. At its core, my dissertation tackles tough questions about local [political] autonomy, the legacies of white supremacy, and organized resistance.

What motivates your research?

Like many Black women, I’ve had a lot of bad jobs. When I was 16, I worked at a childcare center in a gym. A white woman left a review that they didn’t feel safe leaving their child with me because I didn’t “smile enough” ($7.25 per hour). I spent a brief stint interning in a law office. I quit once I was informed that the office cats that wandered in and out of the building throughout the day had infested the office with fleas; I had been itching for days ($9.00). I was a server at a seafood chain where sexual harassment and worker abuse happened almost daily ($2.35 + tips). Not once did I think these experiences were extraordinary. Nor did many other people.

The Charleston Hospital Strike 1969 | Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. (2)

In a way, my research helps me process the trauma of being an unprotected worker in these spaces and understand the mechanisms that allowed these conditions to be normalized. But I also think my experiences mirror broader, systemic trends of devaluing workers—especially workers on the socioeconomic margins. I hope to shed light on how labor valuation is litigated in state and local policy arenas and create a pathway for policymakers and organizers to prioritize worker justice.

Why the South?

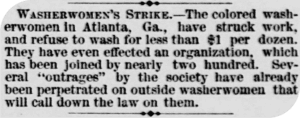

My research is a love letter to the South. The South is home; it bears my family’s blood, sweat, and tears. It birthed my mother and her mothers before her. It is where I found joy, my passion for social justice, and my husband. The South is where I found myself. My work is motivated by a desire to showcase the region’s past and present as a cradle of radical resistance. I do not wish to erase the socioeconomic and racial oppression that is part of the Southern and U.S. narrative. The confederate flags do fly high in Dixie, cotton fields remain, and there are more than a few adopt-a-highway projects sponsored by the Ku Klux Klan. However, Black and Brown Southern workers have long subverted the tyranny of white supremacy through both everyday acts of resistance—what Robin D.G. Kelley refers to as infrapolitics—and mass mobilized movements like the Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike or Bamazon Unionization.

Article from The Washington Star about the Atlanta washerwomen’s strike, August 9, 1881 (3)

The South is home to a growing cadre of free stores, community centers, worker centers, and [other]mothers standing in solidarity against systemic oppression. Through my work, I hope to contribute to a paradigm shift that amplifies the narratives of Southerners working tirelessly for freedom and liberation.

Black History Month Theme

I’m ecstatic that this year’s Black History Month theme is “African Americans and Labor” (ASALH, 2025). Scholars like Angela Y. Davis, Tera Huner, Robin D.G. Kelley, and others have shown that even in the forced confinement of slavery, Black folks have found ways to leverage their community networks and labor to resist oppression. I’m overjoyed that Black labor and labor resistance are finally being highlighted on a national scale.

Health Policy Research Scholars

Resha at HPRS Summer Institute in Baltimore

My work is not conventionally health-focused. However, it has important implications for the overall well-being of Black and Brown communities, particularly as so much of our physical and mental health is bound up in our economic stability. I am grateful for the cross-disciplinary home that HPRS provides. The program has been incredibly supportive of my work and has shown a deep commitment to supporting students whose research intersects with the culture of health more broadly.

(1) www.exhibitions.lib.umd.edu/unions/social/african-americans-rights

(2) www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/the-charleston-hospital-strike-1969/